Table of Contents

The U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation held a hearing on September 3rd, titled "There’s a Bad Moon on the Rise: Why Congress and NASA Must Thwart China in the Space Race", aimed at figuring out how to win the 21st-century "Moon race".

Much of the hearing was focused on maintaining American preeminence in the so-called ultimate high ground of space, fear-mongering about a loss of that preeminence, and maintaining jobs through an active industrial base supporting space. Vague and unspecific mentions were made on how to improve or accelerate the U.S. lunar program, known as Artemis.

However during the hearing, former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine was particularly critical of the choice of SpaceX with Starship for the Artemis program's first lunar lander, and its selection being approved while no administrator was confirmed. In his view, needing to launch a depot Starship, followed by an unclear number of refueling Starships before a crew-rated lunar lander Starship even launches, allows China to land on the Moon before the U.S. this century.

These discussions to win a perceived space race, not even putting forward concepts of a plan to do so, come after the current NASA leadership stated that it wants to violate international space laws to claim parts of the Moon for America's sole use. That was followed by a swift self-gutting of the space agency via the ignoring of federally allocated funding, at the levels of the Trump Administration cuts for the coming fiscal year.

With the Artemis program on its current course, it's possible China may land on the Moon ahead of an American effort this century, largely due to problems with U.S. hardware development and the political environment.

Artemis' problems

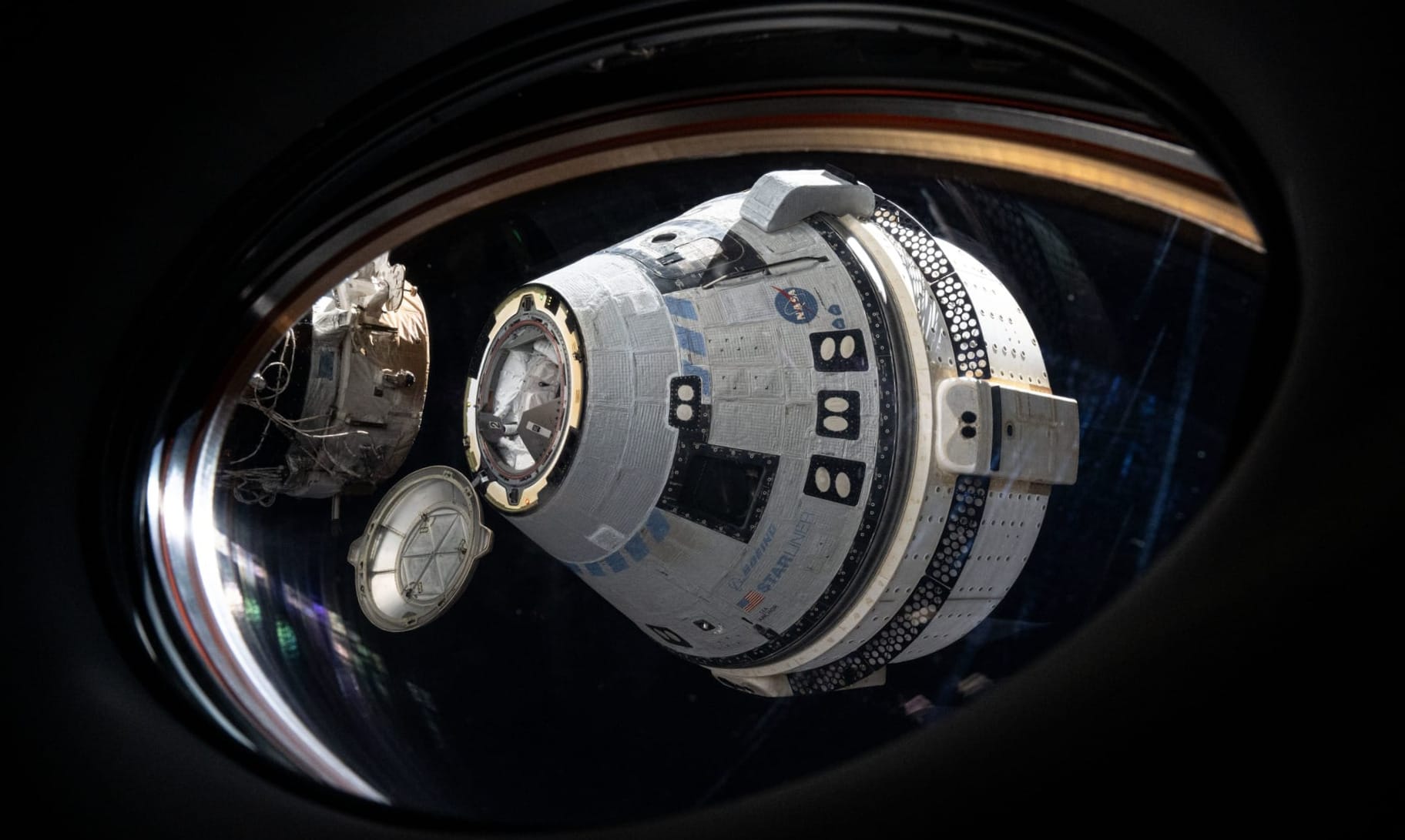

So far, the Artemis program has only two pieces of mission-critical hardware flying: the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and the Orion crew capsule. Both vehicles flew the program's debut mission in late 2022, working almost flawlessly throughout (unexpected char loss during reentry). The two vehicles are almost ready to fly again, this time with crew, having just a few more integration operations left ahead of launch in early 2026. Hardware is also being prepared for the third mission, one to land on the surface, for a 2027 launch.

Of course, SLS and Orion are only half of the process of getting American astronauts to the lunar surface, with a lunar lander version of SpaceX's Starship set to carry out a Moon landing in 2027 at the earliest, following an uncrewed demonstration. Despite being of critical importance, Starship has regressed on any potential progress this year, as in June, Ship 36 unexpectedly exploded during a routine test, wiping out a critical pre-flight test stand with it. Before that, during flight tests of the vehicle, Ship 33 was lost due to a fire in its engine section in January; next in March, Ship 34 was again lost in a fire again; then in May, Ship 35 was destroyed during atmospheric reentry following leakages across the vehicle. Finally in August, 2025's first successful flight test was performed, although only with one more vehicle ready before another design overhaul to meet the capabilities needed for the fully reusable rocket to work as designed. As such the next flight test will likely be a repeat of August's, before another may be performed with new vehicle designs on the same trajectories flown so far.

Making things worse, Starship is not the only part of the U.S. lunar program facing issues. One of NASA's commercial spacesuit providers, initially producing suits for the International Space Station with plans to evolve it for lunar use, dropped out in 2024 due to falling behind set schedules. The remaining space suit provider for lunar missions, Axiom Space, is also facing schedule issues, alongside financial challenges from its many programs.

China is going

Meanwhile, China is taking gradual steps towards sending people to the Moon, having flown a highly successful robotic program. Following various smaller individual tests, the Mengzhou crew capsule performed an abort test in June, the Lanyue lunar lander completed various take-off and descent tests in August, and the Long March 10 completed its first static-fire in August too. That is all alongside utilizing existing hardware for bringing existing reliability into the lunar program, and testing critical hardware elsewhere first as well.

Despite recent strides in hardware testing for the country's Moon missions, China does not view its lunar program as in a race with the U.S. one, due to political factors. China treats its lunar program as part of long-term national development plans with a centralized system that allows for stable, multi-year planning through the Communist Party, National People's Congress, and advisory bodies that set consistent objectives. This contrasts sharply with America, where NASA faces shifting political priorities every four to eight years, meaning the lunar program and others must win support from changing administrations and Congress, making long-term planning difficult. Chief Designer of China's Lunar Exploration Program, Wu Weiren, observed this and noted:

“When the president changes, his policies change,” — “We in China may anchor our goals and always draw a blueprint until the end, so we have always moved forward smoothly and firmly, which is the difference between our two countries.”

Thanks to the political support of China's lunar program, the nation already has a rough roadmap to build its International Lunar Research Station, with various global partners, from 2026 through to the 2040s. Beginning with Chang'e 7 next year, that mission will investigate the lunar south pole environment and catalogue its resources, followed by Chang'e 8 in 2028 to test in-situ resource utilization. In the 2030s, at least five missions will conduct a plethora of scientific experiments to better understand the Moon and its resources, while being supported by a comprehensive communication and navigation constellation. Lastly around the 2040s, long-term human stays are set to be possible to expand the areas of scientific research performed.

Over in the U.S., plans for a sustained lunar presence are small and limited, with an occasionally crewed lunar space station and small commercial robotic landers that fail more often than not. America does boast its fifty-six nation non-binding Artemis Accords however, although not an international effort to build a lunar base, rather to rewrite the space law through its lackluster points.