Orbital Data Center: Innovation, or IPO Theater?

With the boom in AI and the rapid rise in demand of data centers, companies are starting to look to the heavens as the future haven of computation.

With the boom in AI and the rapid rise in demand for data centers, companies are beginning to look to the heavens as a potential future haven of computation. On Earth, data centers are driving higher energy prices, occupying vast amounts of land, and increasingly impacting local communities.

This raises the question: What are space-based data centers, and are they a viable solution?

In the end, space-based compute might be an essential element of humanity's development beyond Earth. However, presenting it as an immediate solution to the burden on terrestrial data centers risks conflating short-term market narrative with long-term industrial ambition. The current drive for orbital computing infrastructure reflects both engineering necessity and pressure from the AI industry's financial and competitive landscape.

What Are Data Centers?

Before examining space-based data centers, it is essential to define conventional ones.

Terrestrial data centers are large facilities that often exceed 100,000 square feet. Thousands of server racks with processors, memory, and storage devices are housed in these facilities, all operating in parallel to tackle complex computational tasks.

In addition to servers, current data centers have sophisticated cooling systems, ventilation infrastructure, backup generators, uninterruptible power supplies (UPS), and fire suppression systems. This integration of systems renders data centers more analogous to living organisms than to traditional buildings.

The Strain on Terrestrial Infrastructure

Operating facilities with thousands of continuously running GPU clusters is resource-intensive. Much of this strain is increasingly driven by AI model training and inference workloads. Which demand far higher compute density per facility than traditional web services.

Energy Cost

Running a data center can require anywhere from 5 to 100 MW of power, depending on its size and purpose. In 2023, data centers used 178 terawatt-hours of power. For comparison, New York City consumes about 48 TWh annually. And analysts predict that by 2030, that number will triple, accounting for up to ~12% of US energy expenditure, driven by accelerating AI energy consumption.

As it stands, over half of all energy consumed by data centers comes from non-renewable sources. The sheer demand from AI has driven energy costs for consumers near data centers to spike, with some areas' wholesale energy prices rising as much as 267%.

Land Impact

In addition to substantial energy consumption, data centers typically require significant land, averaging 10 to 40 acres. However, AI-focused data centers are pushing the envelope, with some planned facilities occupying 200 to 500 acre plots of land.

As of this writing, the largest AI data center is Amazon’s $11 billion Project Rainier in Indiana, which spans 1,200 acres.

Water Usage and Environmental Impact

Data centers also, on average, consume approximately 5 million gallons of water daily, equivalent to the usage of a city with 50,000 residents. Companies are attempting to mitigate this demand by reusing water and utilizing treated water instead of fresh sources.

As demand increases, particularly in water-stressed regions, local communities may be adversely affected.

Overall, these massive facilities exert a significant environmental impact. Current reports attribute approximately 1–2% of global greenhouse gas emissions to data centers, with projections indicating this figure may double within the next five years.

One estimate projects that annual CO2 emissions from data centers will reach 2.5 billion metric tons by 2030, a figure comparable to the emissions of the airline industry.

Control the Data Center, Control the Future

According to Fortune, the total worldwide investment into data centers from 2025 to 2030 is likely to be upwards of 6 trillion USD.

The accelerated demand for computing power is primarily driven by the AI boom. For example, companies such as Micron have discontinued public-facing services to focus on growth in the large language model (LLM) sector.

Concerns in Western countries often arise from the rapid pace at which competing nations, such as China, construct data centers. Leveraging modular construction and significant industrial capacity, China can complete a data center in approximately six months, compared to about three years in the United States.

Some states in the US have even placed building restrictions on data centers—arguing that more permits and deliberation are required due to the harmful nature of these mega-structures.

Some argue that these challenges are an inevitable consequence of pursuing artificial general intelligence (AGI). However, the current rate of data center expansion is unsustainable.

AI companies continually strive to develop more advanced models, which necessitate larger facilities, increased chip production, greater bandwidth, and expanded computational resources to maintain a competitive advantage.

Space to the Rescue?

The concept of deploying computational infrastructure in space is nothing new as in theory, space offers several advantages.

Such as: access to continuous solar energy in certain orbital regimes and effectively unlimited physical expansion.

But these advantages are frequently presented without equal attention to the physical and economic constraints of orbital infrastructure.

Space is not a vacuum of regulation or physics. It simply offers a different subset of engineering problems.

How a Space Data Center Works

Currently when it comes to space-based computing there are two main paths to implementation.

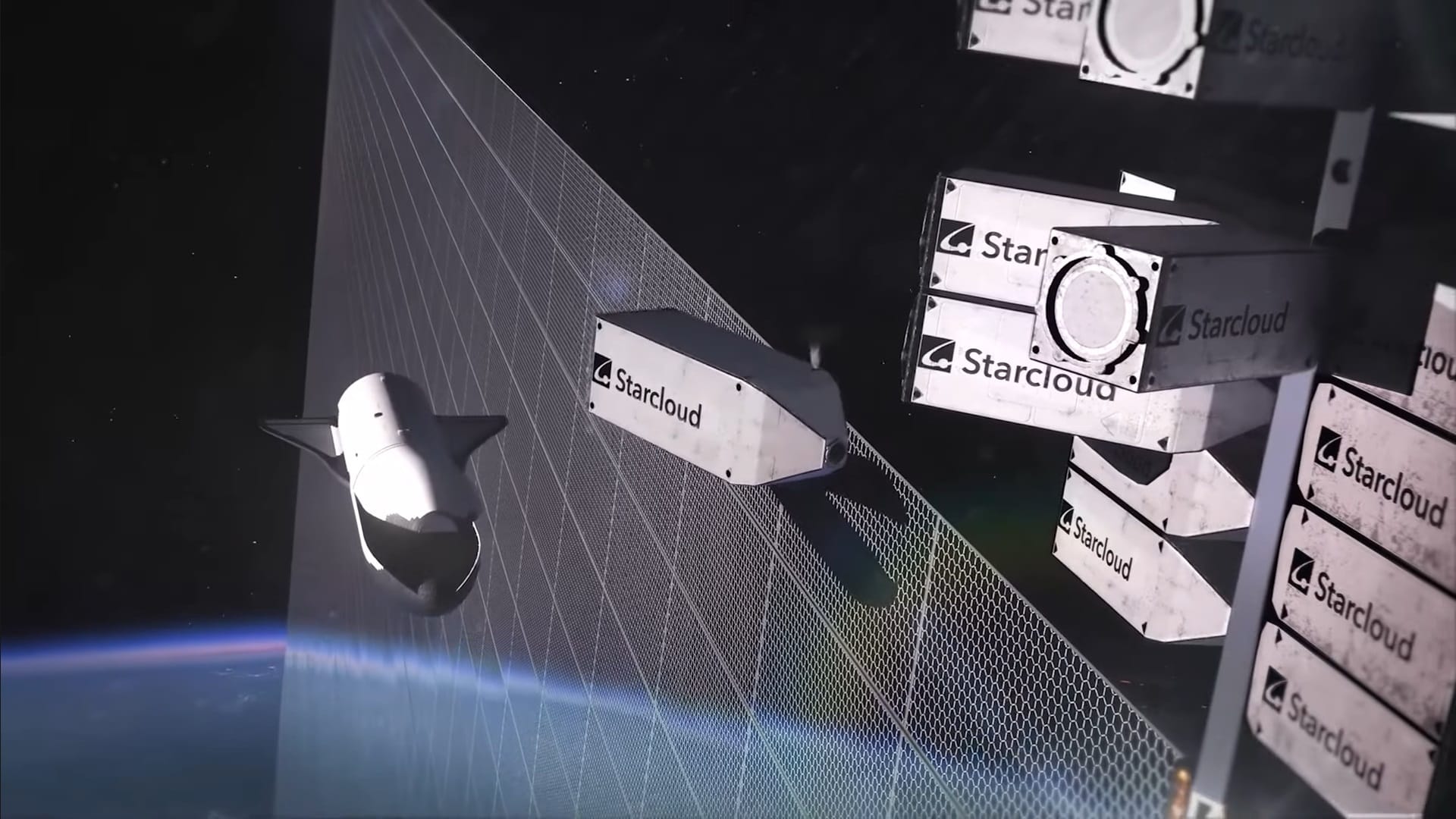

Large Satellite, Small Constellation

Companies like Starcloud are looking to build giant 5 GW satellites to increase compute capacity. These satellites would boast truly immense solar panels and radiators measuring 4km by 4km each.

This has a few benefits, such as fewer bandwidth issues and an upgradable design, as new computational "bricks" can be sent to maintain high capabilities. However, these massive satellites pose many technical challenges, including in-space construction.

Small Satellite, Large Constellation

Rather than building large facilities with extensive solar arrays and radiators, the prevailing strategy is to deploy constellations of smaller satellites in orbit.

These satellites would receive a prompt, communicate with one another, and then send the data back to a user. While much less technically demanding, issues like bandwidth are much more prominent.

As of this writing, several space computing satellites have been launched as test beds for future constellations. Notable missions include:

HPE SpaceBorne Computer-2 and AWS Snowcone (2021-22)

HPE SpaceBorne was the first edge computing system sent to the ISS to support Astronauts during their missions by providing on-orbit data analysis and processing. For instance, ML programs would inspect Astronaut gloves after EVAs to maintain their condition. A year later, “Snowcone” was sent to the ISS during AX-1; this system enabled in-orbit cloud computing for Amazon’s AWS.

Starcloud-1 (2025)

Launched at the tail end of 2025, Starcloud-1 was the first satellite to run an Nvidia H100 GPU in orbit, preluding the company's long-term plan of massive data centers in orbit.

Three-Body computing constellation (2025)

A constellation of 12 satellites operated by ADA Space. In January of 2026, this constellation employed Alibaba’s Qwen3 AI LLM, allowing complex tasks to be computed in space with results sent back to Earth.

Pros and Cons of Space Computing

Space-based computing presents both potential advantages and serious drawbacks.

Pros

- Unmatched scalability

- Doesn't impact local communities or the environment.

- Cost to orbit is lowering

- Solar power in the right orbit is near constant

- Limited permits

Cons

- Hardware cannot be upgraded (at least as easily) and must handle much more strenuous environments.

- Technical hurdles (Cooling, in-space manufacturing, bandwidth, etc.).

- Cooling requires massive radiators.

- Solar flares and space debris can handicap capabilities.

- Lower lifespans than terrestrial variant

- Still more expensive than traditional data centers

Technical and Economic Hurdles

Communication bandwidth, ground infrastructure, in-space construction, logistics, and the harsh space environment collectively pose a significant technical challenge for orbital data centers.

Launching the necessary tonnage is only one piece of the puzzle. Operators also need to mitigate risk, maintain robust constellations, ensure cybersecurity across space-ground linkages, and deorbit hardware in a suitable fashion at the end of its lifespan.

While space-based compute may represent a long-term strategic pathway, it is not a simple or immediate solution to terrestrial constraints.

The Cooling Problem

While space is typically cold, it is also a vacuum. There is no air to carry heat away through convection.

Heat must instead be radiated away as infrared energy. This requires large surface-area radiators. The higher the compute density, the larger and heavier these radiators must be, increasing mass-to-orbit requirements.

Every kilowatt of computing power demands thermal management, and thermal management in orbit demands mass.

Latency and Bandwidth

Even in low Earth orbit, data must be transmitted to ground stations and then routed through terrestrial fiber networks.

This introduces latency and bandwidth constraints. For many real-time or high-throughput commercial workloads, terrestrial fiber remains faster, cheaper, and more reliable.

Space-based compute does not eliminate Earth-based infrastructure—it simply adds another layer.

While I am not doubting the capability of engineers worldwide to solve these technical limitations, it raises an important question: why is space compute being framed as imminent?

Is Prioritizing AI a Viable Business Model?

With talks about the largest IPO in history, the recent acquisition of xAI, and the switch in focus to the Moon, SpaceX has seemingly gone all in on space compute.

The company recently filed a request with the FCC for permission to deploy a one-million satellite constellation into orbit for space compute. The company recently held an internal meeting with employees that included a render of a mass driver on the Moon, with the text: "1,000+ TW/year of AI satellites into deep space."

While there is no doubt in my mind that the company still intends to land humans on Mars, the rapid switch towards AI and going public despite the turmoil that has brought other aerospace IPOs is a little jarring.

The timing is likely not a coincidence. As enthusiasm for artificial intelligence surges, increased attention to orbital compute could influence how investors perceive long-term growth potential ahead of any future public offering.

As organizations across the board establish their roles in the AI ecosystem, ambitious orbital computing concepts garner considerable media and investor attention. In some cases, space-based data centers are framed as “transformative solutions” to Earth-bound constraints.

However, portraying orbital infrastructure as an imminent remedy risks obscuring the underlying driver: exponential AI scaling.

Rather than reassessing demand growth, efficiency optimization, or grid modernization, the solution is externalized into orbit. The physical strain created by AI expansion is not eliminated—it is relocated.

This does not mean space-based computing lacks long-term merit. Rather, current narratives may be running ahead of engineering and economic reality.

Hype vs Horizon

In the end, space computing is neither fantasy nor miracle.

It is a technology that will play a long-term role in the industrial development of human civilization beyond Earth. However, it is neither a short-term solution to the stress on terrestrial data centers nor a replacement for sensible energy planning, hardware efficiency enhancements, and reasonable AI development projections.

Orbital compute may be a part of the horizon.

For now, however, space data centers remains governed by technical hurdles, economics, and infrastructure constraints that no narrative can bypass.

When looking toward the stars, we must remain anchored to the physical limits that shape our ambitions here on Earth.